The Hollister Site is a large 17th-century farm complex situated on the east bank of the Connecticut River in present day South Glastonbury. This area, once known as Nayaug, is part of the 17th-century territory of the Wangunk and other closely related Indigenous groups historically known as the River Indians. The site was occupied by English colonists from as early as the 1640s to about 1711. Since that time it has lain largely undisturbed in a pasture. Archaeological work at the site has uncovered a rich material record of life at the site in the 17th century. Through excavation and documentary research on the history of the site and its residents, we’re learning about daily life in the 17th-century, including architecture, foodways, farming and animal husbandry practices, and trade. The material record of the site also sheds light on the economy of early Colonial Connecticut and the complex relationships among the various groups of people on the landscape including English settlers, Indigenous groups, and the Dutch.

Lieutenant John Hollister

Lieutenant John Hollister arrived at the young settlement of Wethersfield Connecticut from a village near Bristol, England around 1642. He married Johanna Treat in 1643 and was admitted as a freeman the same year. According to Wethersfield land records the Hollisters had acquired 23 parcels of land totaling about 240 acres. Sixty acres of this land included a working farm located at Nayaug, on the east side of the Connecticut River. At the time, Nayaug (now South Glastonbury) was part of Wethersfield and many property owners held farm, pasture and woodlots on this side of the river.

John Hollister likely purchased the Nayaug farm prior to 1650, but the exact date is unknown. The Hollisters were not the site’s first English owners. The early history of the property is poorly understood due to scarce and incomplete records, but Wethersfield land records note that the 10-acre parcel containing the farm was purchased “…in exchange of William Gibbons of Hartford, wh he bought of Mr Denton: containing the whole accommodations of all the mea: wh the said Denton had on this side the River wh was ten acres…”.

Mr. Denton is the Rev. Richard Denton, who lived in Wethersfield for a short time in the late 1630s and early 1640s before removing to Stamford. Gibbons was a land speculator, who probably purchased the land from Denton with the intent of selling it, rather than using it himself. When John Hollister bought the property, it included a house and outbuildings dating to Denton’s tenure. The term “accommodations” in the land records refers to structures, including those that could serve as at least temporary housing

The Gilbert Family

In 1651 the Hollisters leased the farm to Josiah Gilbert. Josiah was one of five Gilbert brothers who settled in Connecticut in the 1640s and 1650s. A yeoman farm family from Yardley Parish in England, the Gilberts initially settled in Mt. Wollaston, Massachusetts around 1638. By the mid-1640s, the three oldest brothers, Thomas, Jr., Jonathan, and John had settled in Windsor and Hartford, Connecticut. Their younger brother Josiah leased the Hollister farm in 1651 and while John and Jonathan Gilbert maintained their own homes in Hartford, both maintained a financial interest in the farm. The Gilbert parents, Thomas, Sr. and Elizabeth, and youngest brother, Obadiah, also lived on the Hollister farm in the 1650s. The Gilbert family remained on the Hollister farm until 1663.

Many of the large land owners in Wethersfield likely had tenants working their farms and/or herders tending their pastured livestock on the east side of the River. Tenant farmers generally paid their rent either as a fixed portion of farm products, in cash, or as a combination of both. We know from the probate records of Thomas Gilbert and John Hollister, Sr. that in the 1650s and 60s the farm produced livestock, corn, oats, wheat, barley, and hay, dairy products, and honey, and that the property included orchards and pasture.

2016 Field Season

2016 Field Season with excavation areas arranged over the three main cellars.

John Hollister Jr.

When Lt. John Hollister passed away in 1665, his son John Hollister, Jr. received “his house and barn, orchard and pasture” with “sixty acres of plowing and mowing with other land” in Nayaug. John married Sarah Goodrich in 1667 and the couple established a home at the Nayaug farm. John and Sarah Hollister had eight children who lived to adulthood and grew up on the Hollister farm. John likely worked the farm with the help of his two younger brothers, Thomas and Joseph Hollister, until they came of age and claimed their own inheritances.

The farm was fortified with a palisade in 1675 to protect neighboring families and their farm products during King Philips War. During this time, John also aided the local Wangunk tribe with the construction of a palisade on high ground just north of Nayaug. Toward the end of his life, John parceled off his lands to his sons who began to raise their own families nearby. John Hollister died in 1711 and soon after, the house and farm were abandoned. By that time settlement in what was now the town of Glastonbury, had shifted away from the river to the roads of the town center.

Boy Scouts helping in 2016

Scouts helped to excavate a 5-meter grid of test pits around the site to document artifact distribution in the topsoil.

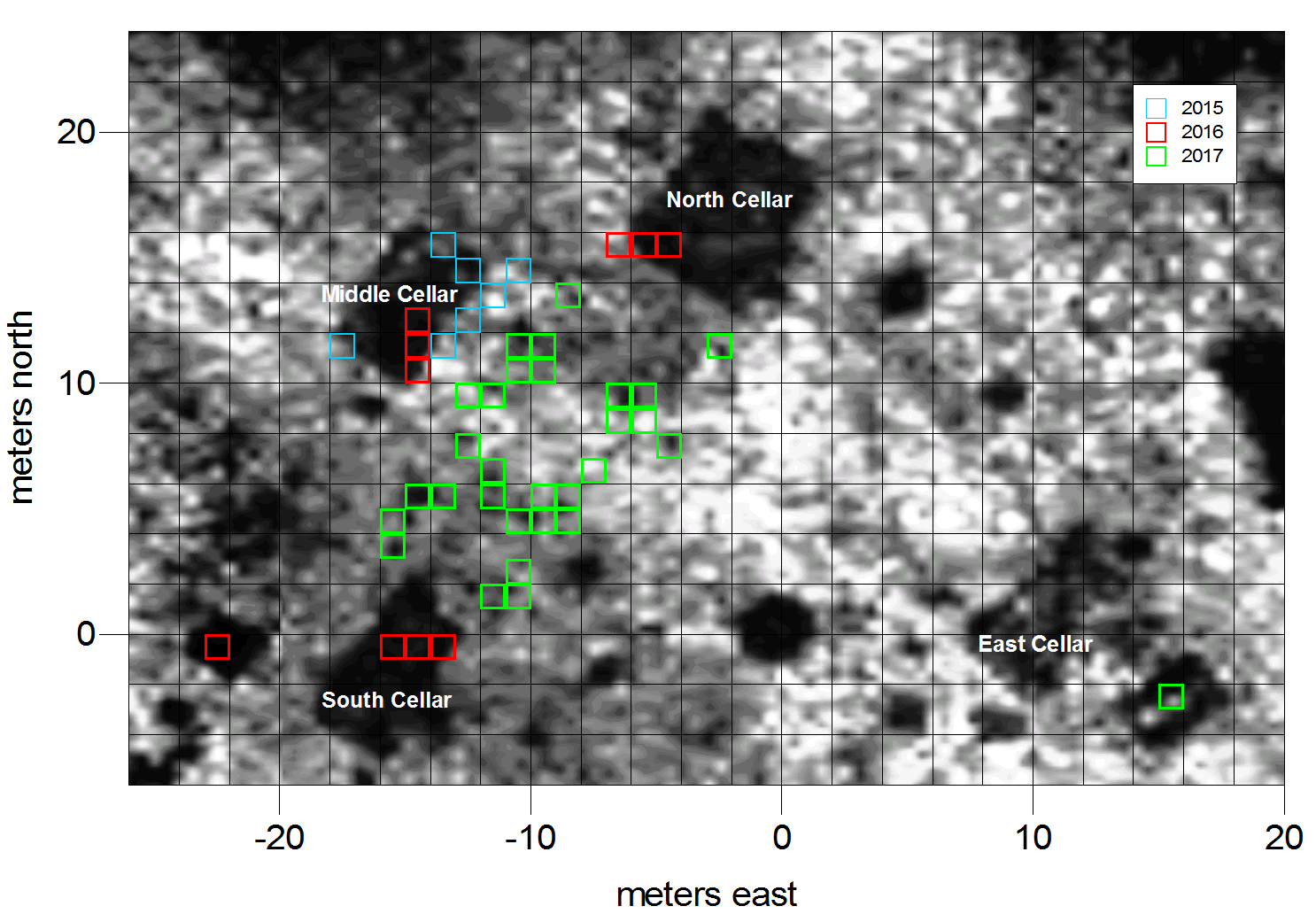

Radar image and excavation areas

Finding the Site & Remote Sensing Investigations

In 2015, the Glastonbury Historical Society and landowner Mark Packard, a Hollister descendent, approached the Connecticut Office of State Archaeology to run a public excavation in the large horse pasture believed to be the location of the John Hollister farm. In preparation for this, I asked UConn graduate student and ground penetrating radar (GPR) expert Peter Leach to survey the area for features that might be worth investigating. That preliminary survey produced remarkable results – three large rectangular cellars were identified, as well as other probable cellar features and a number of large pits or posts. The one-day Historical Society dig produced a small assemblage of artifacts that hinted that this could be the location of the Hollister farm, so a more intensive follow-up study was scheduled for 2016.

The 2016 field season began with a magnetometry study of about three acres of the pasture surrounding the core site area. This work was conducted by graduate students Maeve Herrick and Jasmine Saxon from the University of Denver. Herrick and Saxon followed this study with additional Ground-penetrating-radar work in July and August, expanding on Leach’s original survey. Since then, additional GPR work has been carried out at the site by David Leslie, Cyndall Groskopf, and Eric Heffter and analysis of that data is ongoing.

The remote sensing work at the Hollister Site sheds light on the buried landscape and complex of cultural features at the site. Remote sensing data has been instrumental in guiding the investigations at the site. It has helped to clarify the spatial organization of the cellar features and allowed us to target those features without unnecessarily excavating large portions of the site or stripping off the topsoil, which is important because the site is an active pasture. While the data is extremely useful, it is only the first step. All of the identified soil anomalies must be “ground-truthed” to be certain of their size, shape, contents, and functions.

Public Archaeology at the Hollister Site

The Hollister Site investigation was established as a public archaeology project. Since 2015, the site has served as an outdoor classroom for students, historical society members, scouts, avocational archaeologists, educators, avocational archaeologists, and members of the interested public. The project provides the opportunity for people to work alongside trained archaeologists to learn the basics of archaeological field methods, artifact identification, mapping, and remote sensing techniques.

The Hollister Site also provides a tangible connection to the rich early Colonial Period History of Connecticut. The 17th century was a time of exploration, culture contact, conflict, and struggle. The Hollister site provides the opportunity to explore the material reflections of all of these processes and learn about the early history of Connecticut Colony, the complex Indigenous/English relationships that characterized the period, and about the daily of life of real people who lived along the Connecticut River in the second half of the 17th century.

Excavating the Middle Cellar

Italian marbleized slipware

This uncommon high-status ceramic was manufactured near Pisa Italy between 1600 and 1650.

2016 Excavations

Archaeological excavations were undertaken in August of 2016 through public programs associated with the Connecticut State Museum of Natural History (UConn) and the Historical Society of Glastonbury. The excavation season focused primarily on three cellar features identified in the GPR surveys. The features were designated as the South, Middle, and North cellars and a 1m-x-3m excavation block was placed in each cellar and excavated down to the cellar floor (about 150cm). The South Cellar was plank-lined, while the Middle and North Cellars were lined with stone. The cellar fill, screened through 1/8-inch hardware cloth, contained rich, well-preserved deposits of domestic, architectural, and personal artifacts reflecting life on the Hollister Farm in the 17th century. The recovered artifacts included ceramics, kaolin and red clay smoking pipe fragments, European flint artifacts, trade beads, and thousands of food remains.

[Link to Artifacts] The ceramic assemblages from the cellars are dominated by simple red earthenwares, with a variety of English, Dutch, and Portuguese tin-glazed wares, yellow border ware, Midlands Blackware, Rhennish stoneware, Dutch utilitarian ceramics. Ceramic and faunal cross mends between the South and Middle cellars indicate that these features were filled around the same time.

Food remains from the cellars contained a diverse mix of European domesticates and wild species. While European domesticated animals are present in the cellars, the animal bones were dominated by local wild animals, especially white-tailed deer. We also recovered bear, raccoon, woodchuck, muskrat, skunk, weasel family (like martens, fisher cats, and minks), squirrel, turkey, whistling swan, ducks, passenger pigeons, perching birds, several types of turtles, and a range of large and small fish. The full range of fish have not yet been identified, but we know they ate cod, sturgeon, trout, catfish, and perch. The cellars also contained large quantities of hard- and soft-shell clams and oysters. Identified plant remains included grains like maize, beans, peas, wheat; local nut species including hickory nuts, hazel nuts, butternut, and chestnut, as well as grapes, cherries, and Chenopodium or goosefoot.

Additionally, we recovered several hundred sherds from 17th-century Indigenous pottery vessels. The pots may have been crafted by local Wangunk people who lived in Nayaug near the Hollister farm. The pottery, along with the trade beads found at the site, reflect complex economic, social, and political relationships between local Indigenous people and English settlers in the 17th century.

2017 Field Season

The 2017 field season focused on learning more about the relationship among the three cellars tested in 2016. Given their configuration, we hypothesized that two (or even all three) may have been connected to form one large structure. Volunteer excavators dug numerous units down to the base of the plowzone between the cellars to look for features that may connect them, like posts or wall segments. The excavations revealed an array of posts and pits, as well as the posts from a large 20th century tobacco barn. A larger area around the cellars still needs to be excavated to fully understand their connections.

Additional testing was also carried out south of the main locus of the site, where the remote sensing surveys identified other likely structures. This excavation focused on an anomaly that turned out to be another cellar. Two one-meter units were excavated down to the cellar floor in this feature, which became known as Cellar 5. While the artifact density was not as high as it was in the South and Middle Cellars, Cellar 5 also contained a range of artifacts including ceramics, glass, European flint artifacts, and food remains. Simple red earthen wares dominated the ceramic assemblage, but it also contained English yellow slipware (dates), tin-glazed ceramics, and North Devon gravel tempered ware. Among the more notable artifacts were a Huntress and Crusader pipe bowl, a large earthenware jug, white shell wampum beads. Diagnostic artifacts from this feature, including kaolin pipes and some of the ceramics, indicate that it was filled after 1675.

Pit feature adjacent to Cellar 6.

2018 Excavations

The focus of the 2018 field season was again the southern part of the site in the location of number of large anomalies identified through remote sensing. A large excavation block was excavated down to the plowzone around one such anomaly, which turned out to be another large cellar. The cellar was rectangular and surrounded by numerous posts and at least one large pit feature. Test units excavated into the cellar showed that it was plank-lined like the South Cellar; soils stains from the planks were visible along some of the walls. Surrounding posts indicated that the structure associated with this cellar was constructed using a post-in-ground technique. The units excavated into the cellar produced another interesting assemblage of artifacts and food remains. Artifacts from the cellar fill included a large assemblage of red earthenware, as well as sherds of North Devon gravel-tempered ware, tin-glazed wares, European flint artifacts, kaolin pipe stems and bowls, food remains, and architectural artifacts.

Several datable artifacts from Cellar 6 suggest that this feature was used and filled in during the latter part of the site occupation. We found a pipe marked with LE, for Llewellyn Evans, whose pipes date from 1661-1688. At the very base of the cellar, we recovered a large delftware sherd with the “Chinese scholar” pattern. This decorative motif dates from 1675-1695. Finally, among the most intriguing (and datable) artifacts from the 2018 excavations was a small coin recovered from the plowzone above Cellar 6. This tiny silver coin, which has Arabic script, was minted in 1692 in Yemen. Several of these coins have been found throughout New England and probably arrived in the region as pirate loot.

Feature 20, which was partially exposed off of the southeast corner of the cellar, was also tested and is interpreted as an irregularly-shaped pit. This feature contained a large quantity of red earthen ware and animal bone, along with four small sherds of Indigenous pottery, flat glass fragments, two pipe bowl fragments, a piece of scrap brass, and a nail.

Images from the field include ceramics, small finds, clay pipes and photos of the excavations. When considered along with the materials recovered from cellar 5, the artifacts from this southern portion of the site suggest a somewhat later date of activity in the last quarter of the 17th century. The abundance of large red earthenware sherds from these cellar features suggest dairying activities may have occurred in that part of the site.

2019 Field Season

The 2019 excavation season focused on the area just north of Cellar 6. A large block of excavation units was excavated down to the base of the plowzone to expose cultural features and recover a sample of cultural materials. The recovered artifacts included a range of ceramics including several sherds from a North Devon gravel-tempered ware jar, a large assemblage of coarse red earthenwares, German stoneware, tin-glazed wares, manganese mottled, and English yellow slipwares with dot, combed, and reverse patterns. We also found animal bone, European flint, architectural artifacts, and glass fragments.

The 2019 excavations uncovered the northeast corner of Cellar 6, along with two large features. We found a series of large, flat stones, extending north in a straight line from the corner of Cellar 6. These are interpreted as possible footings for an addition to the structure over the cellar. Another large, flat stone was also tipped into the edge of the pit feature (Feature 34), forming a right angle with the others. We believe that these stones may have supported posts.

The other identified features included a large pit with deer bones visible at the top (Feature 34), and a likely pre-contact Indigenous hearth filled with fire-cracked rock and charcoal (Feature 35). Unfortunately, there wasn’t time to investigate the two features in 2019. The fire-cracked rock feature is probably associated with the earlier Indigenous occupation of the landform containing the Hollister Site. All of our excavations have resulted in the recovery of lithic artifacts dating primarily to the Late and Terminal Archaic periods (about 3000-6000 years ago). While we suspect that Feature 35 significantly pre-dates the English occupation of the Hollister Site, the feature will be radiocarbon dated to provide a definitive answer.

2021 Excavations

The 2020 field season was cancelled due to the Covid-19 pandemic, but we returned to the site in 2021. We focused our efforts on learning more about the South Cellar, the plank-lined cellar feature tested back in 2016 We excavated 28 square meters around the cellar feature down to the base of the plowzone, to expose features related to the cellar and help us better understand the former structure. Like Cellar 6, the South Cellar was built using earth-fast or post-in-ground construction methods. Numerous posts were found around the cellar, along with several other interesting features. The most interesting and informative of these was feature 38, which abuts the north wall of the cellar. This feature appears to be a shallow, sloping entrance into the cellar. Investigation of Feature 38 revealed soil stains from 2-3 wooden steps that led down into the cellar. Posts along the edges of this feature suggest that it was probably covered by a wooden structure.

We also found another fire-cracked rock hearth (Feature 68), adjacent to the east wall of the South cellar. While the results of radiocarbon dating are not yet available, this feature, like Feature 35, may be an ancient Indigenous hearth. A large circular pit (Feature 70) was identified adjacent to the east wall of the South Cellar, but we didn’t have time to investigate it in 2021. Finally, we also identified Feature 69, a long, linear stain that appears to extend out to the northwest and southeast from the southern part of the cellar. Posts are visible along the edges of the stain, suggesting it is a wall structure. At this point, however, it is unclear if the wall is associated with the South Cellar, or if it represents a later fence or palisade that was built over the top of the cellar after it was filled in.

The artifacts recovered around the South Cellar and in Feature 38 suggest that it may be among the oldest English structures at the Hollister Site. Artifacts include the typical range of materials from this part of the site: clay pipes, food remains, architectural items, European flint debitage and gunflints, trade beads, Indigenous ceramics, and European ceramics, including red earthenwares, a variety of English, Dutch, and Portuguese tin-glazed wares, border ware, Rhennish stoneware, and a small number of Dutch utilitarian ceramics. One intriguing artifact was a large chunk of coral found in the top of the South Cellar fill. The coral originated in the Caribbean and like reflects early colonial trade with the West Indies.

2022 Field Season

In the 2022 field season we had three main goals: to expose more of the area around the South Cellar to look for features, to investigate the pit (Fea. 70) and fire-cracked rock (Fea. 68) features identified in 2021, and to excavate three additional one-meter units in the Middle Cellar (initially excavated in 2016) to increase the assemblage of Indigenous pottery.

Feature 70, which was located adjacent to the east wall of the South Cellar was bisected, drawn and photographed in profile, and then excavated. We took a number of soils samples for flotation, but those have not yet been processed. This circular pit feature contained a small assemblage of cultural materials, as well as numerous chunks of daub. Daub is a sticky material made from clay, sand, straw and/or other materials. It was used in an ancient construction technique that was still employed in the early colonial period Chesapeake and New England. Walls woven from a lattice of wooden strips or twigs (wattle) would be covered with daub. The daub would dry and harden and often be covered with a whitewash to increase the lifespan of the walls. The daub we found looks to be tempered with crushed shell and was probably used to construct parts of the earth-fast structures at the site, including the South Cellar.

The biggest surprise in 2022 was the number of 17th-century indigenous artifacts we found mixed in with the English materials at the Hollister Site. In 2016, numerous large sherds of 17th-century Indigenous pottery were found at the base of the Middle Cellar. This season, we excavated another 1m-x-3m area adjacent to the previous excavation and down into the cellar fill. We encountered similar layers of ash- and charcoal-rich soil and extraordinary preservation of artifacts. While we only recovered a few sherds of Indigenous pottery this year, we found stone tools knapped from European flint, numerous wampum beads and likely evidence of wampum manufacture on site. In other areas we also recovered brass and lead pendants, several pieces of worked scrap brass, and two brass arrow heads.

It is clear that the Hollister Site contains material information reflecting the complex social, political, and economic relationships between English settlers and Indigenous people in Colonial Connecticut and we are focused doing additional historical research to contextualize these materials and better understand what was going on at the site. Stay tuned!

View a sample of artifacts and cultural features from the 2022 field season.

Ongoing Research

The Hollister Site is arguably one of the state’s most significant because of its age, richness, and lack of subsequent disturbance. In terms of material culture, it is perhaps most comparable to the Governor Sir William Phips Homestead in Woolwich, Maine (examined by Robert Bradley), the Chadbourne Site in South Berwick, Maine (examined by Emerson Baker), and the Sylvestor Manor Site on Shelter Island, New York (Fiske Center, UMASS, Boston). Architecturally, the three cellars at the core of the Hollister Site may prove to reflect a very long West Country style “cross-passage” house, but further work will be required to determine if the three aligned cellars formed part of a single household structure or not.

The heavy reliance on wild animal foods on a large colonial farm site raises several interesting questions about the economic activities, food procurement, and foodways at the site. If domesticated animals were raised on-site, why were so few of them eaten? Were the Hollister Site residents raising their animals for commercial trade? If so, where and to whom were those animals sold? Who was doing all of the hunting and fishing at the site? Is there an Indigenous influence to the diet? (Among others!)

Increasing evidence of a contemporary Indigenous presence at the site also raises many questions. The quantities of contemporary Indigenous pottery, worked scrap brass, brass arrow points, scrapers and utilized flakes made on European flint, and evidence of wampum production may have come from Native people living on the site during the Gilbert and/or Hollister occupations. If so, the nature of those relationships might have been cooperative, economic, or coercive. Additional historical research is needed to flesh out our understanding of the interactions between the Gilberts, Hollisters, and their Wangunk neighbors.

Analysis of the materials recovered from the site is ongoing. We plan to revisit the site for additional fieldwork in the summer of 2023.