Emergency excavation at the Dug Road Site

Site History

In the Fall of 2014 the Office of State Archaeology was notified by a Glastonbury resident that charcoal stains had been exposed by recent construction activity. Examination of the site quickly determined that trenching for a drainage line had in fact impacted a Native American site consisting of scattered cooking hearths and other features. OSA coordinated with the town engineer, SHPO, tribal representatives, and the construction personnel to develop a plan to permit a rescue excavation of the site. Town workers used their equipment to carefully remove topsoil from areas to be impacted by remaining construction activity, and construction work was moved to a different location while the state archaeologist and FOSA volunteers documented the site. Work at the site continued continued from mid October through early November. Fourteen features and a variety of artifacts were identified during the data recovery excavation. Features included a number of earth ovens, a possible house floor and some additional small soil stains. Six radiocarbon dates from these features were between 4230 and 3880 years old, reflecting calibrated ages between 4800 and 4200 years ago. The site is interpreted as the location of one or more Late Archaic camps, at least one of which appears to have also included a rectangular living structure, and associated cooking features.

Dug Rd Artifacts

basalt adze

Development of the Connecticut River

This site is just one piece of a much larger story about how people lived in the Connecticut River floodplain during the Late Archaic period, but it is particularly valuable because of its undisturbed condition, and thus offers unique insights into two pressing questions: First, how did it survive millennia of river meanders that have destroyed similar sites elsewhere? Second, how was this area used by Native American people at this time, and why was it such a favored place to live?

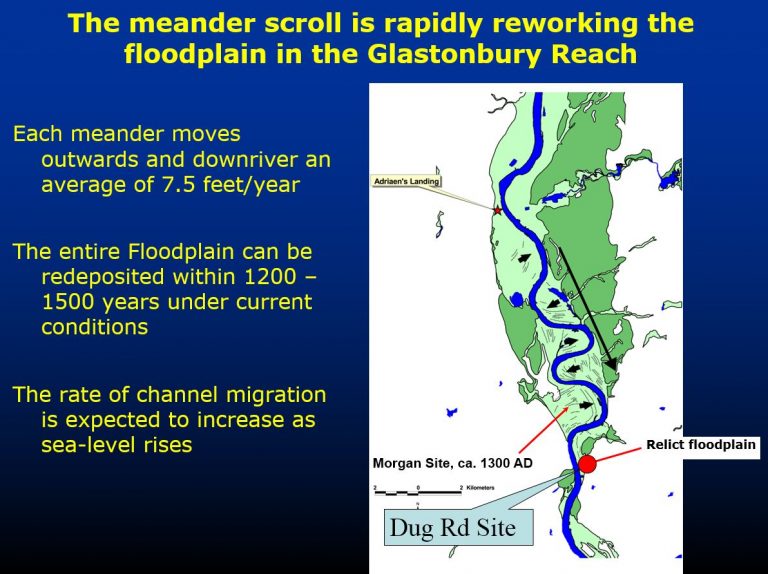

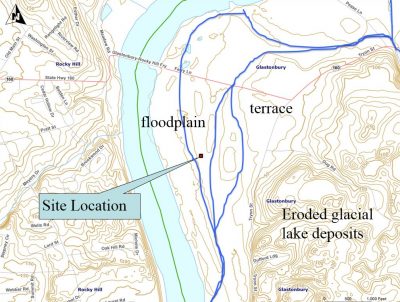

The Connecticut River has a dynamic geological history. Prior to construction of the Connecticut Science Center and Convention Center in downtown Hartford, deep geological core samples were taken and studied by Robert Thorson, Daniel Forrest and myself. The sediments retrieved in those samples document 9000 years of the river’s geological history. What we learned was that between 9000 and 6000 years ago the river flowed swiftly through central Connecticut within a steep channel. That early Connecticut River seldom flooded its banks until about 6000 years ago, when rising sea level began to impede the flow of the river. This marked the development of the meandering river we know today between Hartford and Middletown. Every spring floodwaters topped its banks, gradually laying down many feet of silty sediments. The meandering river ate away at its banks more than seven feet a year, reworking the entire floodplain zone every 1500 or so years. This means that any evidence of settlement on the floodplain was destined to erode over the course of one or two millennia. So how were 5000-year-old sites able to survive in South Glastonbury?

The Connecticut River

A preserved ancient floodplain

A Relict Archaic Landform

Based on nearby finds similar to those uncovered this fall, we know the south Glastonbury floodplain is a precious relict Archaic landscape. Its survival remains somewhat of a mystery, but it is likely tied to the glacial geology of the ancient Roaring Brook drainage just to the north. Roaring Brook once carried a great flood of melting glacial waters from the uplands into the valley bottom. During that episode of dramatic meltwater flow, boulders as large as trucks were pushed downstream. Today the brook flows languidly into the Connecticut River and its shallow muddy bottom can be challenging to navigate even by canoe. Deep beneath those river muds, however, must lie a dense layer of enormous boulders. That deep stony substrate has probably acted as a barrier to the river as it has attempted to meander into this part of the floodplain over the past 5000 years, protecting the archaeological sites to the south.

A special site

The south Glastonbury site therefore represents a very lucky find for archaeologists — a rare chance to examine riverside life as far back as 5000 years ago. But what was it like along the river then, and what drew people to live here? As the Connecticut River began to slow and meander across the valley, it promoted the development of biologically rich habitats. These were the ox-bow lakes and abandoned channels left behind as the river shifted its course. These wetlands developed all along the floodplain, and provided a foothold for an abundance of species to take hold and flourish. The wetlands promoted plant species such as cattail, water lily, and bulrush that provided nourishing edible shoots and tubers to small game animals such as beaver and muskrat, and to the people that hunted them. Waterfowl, freshwater fish, and turtles were certainly common in the oxbows as well. In the nearby river, spawning game fish such as salmon, shad, eels, alewives, and sturgeon could also be taken. Freshwater shellfish remains from the archaeological site and others nearby indicate that these were gathered as well. The floodplains themselves, disturbed each spring by the freshet, offered an ideal open habitat for valuable terrestrial plant foods such as goosefoot, Jerusalem artichoke, and groundnut, as well as important fiber resources such as dogbane. The charred material recovered from the abundant features permitted the identification of plant remains by Tonya Largy. Tonya noted that the most common identifiable plant fragments were from butternut shells. Interestingly, carbonized bark made up between 40% and 95% of the botanical remains examined. It is possible that the bark was used to insulate the earth ovens during use. In sum, the meandering Connecticut River floodplain provided a wealth of resources to the hunting and fishing communities of the Connecticut River.

Site Interpretation

To fully interpret the Glastonbury site requires a clear understanding of both the geological changes in the Connecticut River, and the environment that developed along its banks. First, understanding the dynamic history of the river increases our appreciation of the rarity of this remnant ancient landform. Elsewhere along the river evidence of Archaic period daily life was eroded away thousands of years ago. Second, the site itself represents a small, but very important glimpse into daily life in this part of the state nearly 5000 years ago. The evidence of a living structure suggests family sized groups stayed here for fairly long periods of time, most likely during the summer months after the threat of flooding had passed. Its rectangular shape suggests a small “longhouse” type of arched pole architecture, rather than the round wigwam most of us are familiar with among Algonquian peoples. The adze, and other artifacts like it in the Horton collection, indicates that woodworking was an important activity – probably for the manufacture of dugout canoes. Two types of food processing are reflected in the features we found. Within the household area, cooking utilized heated stones, perhaps used to boil stews in leather or bark containers. The deep “earth ovens” suggest that other foods, probably starchy tubers, were baked for long periods of time surrounded by hot coals.

earth oven feature