Two weeks ago as I write this I chaired a session of the annual meeting of the Society for Historical Archaeology in New Orleans titled “The John Hollister Site: A 17th Century Fortified Farm Complex in Glastonbury, Connecticut.” The session was devoted to preliminary analysis of work conducted at the since 2015. This was a special chance to let archaeologists from across the country know about this important new site, as well as an important opportunity for graduate students and recent post graduates to present their research. For those unfamiliar with the John Hollister site, it is an expansive 17th century farm complex located beside the Connecticut River in South Glastonbury. The site has yielded extraordinarily rich information about this poorly documented period of English settlement in Connecticut.

Introduction

Introduction

The two-hour session began with my own short introduction to the site. In the talk I summarized the history of English land ownership and associated probates, noted the history of archaeological work conducted to date and the overall layout of the farmstead, and presented images of some of the most interesting artifacts from the site. These include a variety of clay pipes, delftwares, slip-decorated wares, stoneware and glazed red earthenwares. Some of these ceramics have so far defied clear classification, and feedback from the audience has helped move our exploration of their origins in some new directions. I finished by noting the site’s significance to both Connecticut and the broader Atlantic seaboard’s understanding of this important phase of English (and Dutch) settlement in the region.

Remote Sensing

This was followed up by a talk by Peter Leach (UConn) coauthored by Maeve Herrick (University of Denver) and Jasmine Saxon (University of Denver) . Leach, Herrick and Saxon summarized the remote sensing work conducted in 2015 and 2016, including magnetometry and ground penetrating radar. The talk discussed the use of these methods not only for identifying subsoil features, such as the five cellars, two wells, many large pits and probable wigwam structures associated with the site, but also their use in better understanding the underlying geology of the site. They noted that the core area of settlement is located on a slightly higher moraine-like glacial landform bounded to the south and north by water-lain sediments filling relict channels. The paper was largely an encapsulation of Herrick’s recent Master’s Thesis from the University of Denver. One of her key findings was the presence of a fifth stone-lined cellar well south of the core habitation area, as well as three nearly adjacent probable Native American house floors. These appear in radar to be semi-subterranean wigwam-like oval structures, and limited testing conducted this summer established that at least the central feature is contemporaneous with the rest of the Hollister Farm settlement.

Faunal Analysis

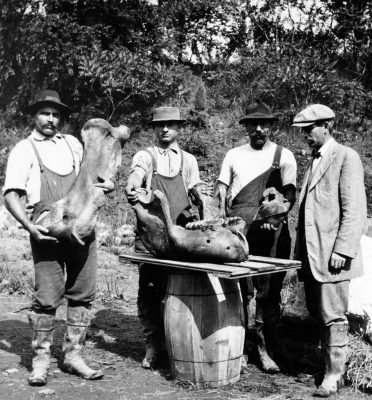

Sarah Sportman (AHS, Inc.) then summarized her preliminary examination of faunal remains from the site. Questions that can be addressed through the analysis of the site’s animal bones include the following: 1) what can the faunal assemblage tell us about foodways and diet at the site? 2) what can it tell us about animal husbandry practices? 3) what do the faunal remains tell us about food procurement strategies? 4) what does the assemblage tell us about disposal patterns, site formation processes, and site abandonment? 5) what do the skeletal parts and butchery patterns tell us about food production, procurement, and consumption? and 6) how does the faunal assemblage compare to other known 17th century sites in southern New England? Sportman noted that only about 26% of the bone assemblage indicated weathering on the surface, suggesting that most of the bone was buried rapidly in the cellars. Surprisingly, deer bone made up almost 50% of the identified specimens, indicating the importance of venison in the diet. Bone representation of deer body parts further indicated on-site butchering. Other wild game included raccoon, muskrat, skunk, woodchuck, squirrel and weasel family, as well as a number of small rodents. Noted, but not included in the study, were the numerous shellfish and fin fish remains. Domestic animals, including pig, sheep/goat, and horse made up only 26% of the identified bone. Butchering of the horse and evidence for the focused extraction of marrow also suggested that little food went to waste. This pattern suggests to Sportman a frontier signature, where hunted game still dominated the foods eaten, as domestic animal stocks were still being developed.

Botanical Analysis

This was followed by William Farley’s (SCSU) summary of preliminary identification of botanical remains from the site. Farley posed the following research questions: 1) can we reconstruct the environment of the farmstead? 2) can we reconstruct the diet and daily behaviors of those living and working there? 3) does the botanical data say something about intercultural exchanges and entanglements in 17th century central Connecticut? He noted that the identified plants reflect a variety of open farmland weeds, with fewer forest weeds and just one species of wetland plant, suggesting that the farm complex was largely surrounded by open agricultural fields. Food remains were dominated by maize and hickory nut, indicating the importance of these indigenous plants to the diet. While some beans were also present, the next most common species by count was domestic cherry, followed by grape, wheat and hazelnut. Farley suggests that the plant food remains reflect a diverse diet that combined both indigenous and European food resources. The plant foods do not indicate a focused agrarian lifestyle, but rather a more complex, heterogeneous strategy combining traditional English and Native American crops and wild resources.

Phytolith Analysis

Krista Dotzel (UConn) then summarized her examination of plant phytolith remains from soil samples taken at the site. Phytoliths are microscopic silica bodies that lend structural support to many plants, especially those in the grass family. Dotzel was curious if a phytolith study might indicate the use of plant species not documented in the historical record, such as barley potentially used for local beer making. Phyoliths are hardy remains that have also been used to identify specific areas of plant processing as well as broader environmental information. Her finds indicated the presence of maize in three samples, and wheat in one. Other phytoliths present included sedge family and woody plants, but were not species-specific. Other interesting observations included a very high abundance of phytoliths preserved in a bottle base from which a soil sample was preserved, as well as the presence of abundant fire-altered husk remains (probably wheat) from the ashy lens at the base of the south cellar. Exactly why this burned husk residue ended up on the cellar floor is something of a mystery, but it probably occurred during use of the site.

The Tobacco Economy

Jasmine Saxon (University of Denver) then discussed the role of tobacco smoking and money during the 17th century occupation of the Hollister site. Her talk noted that the second half of the 17th century was one of abrupt economic changes. In particular, the price of tobacco reached a low point in about 1650, significantly affecting the colonial economy. In Virginia, local red clay pipe manufacture increased markedly, reaching a peak around 1680. After this period, the local production of clay pipes declines. She concluded that it was likely that the relatively abundant red clay pipes identified at the Hollister site fit into this general economic pattern during the second half of the 17th century; a time when English imports such as pipes and Virginia tobacco may have become increasingly difficult to obtain, leading to not only local pipe manufacture in Connecticut, but possibly tobacco farming for local consumption as well. Her finds appear to be substantiated by recent pXRF analysis conducted by UConn undergrad Caitlin Kingston suggesting many of the red clay pipes found at Hollister may be of local origin.

Wangunk Interaction

Maeve Herrick (University of Denver) then discussed her analysis of Native American pottery from the Hollister site as a material expression of interaction with the local Wangunk people. Her examination of the sherds indicate that these are best described as Shantok ware, a type defined originally at the Mohegan site of Fort Shantok in Uncasville, Connecticut. This style was manufactured by Native people across much of Connecticut between the Pequot War and King Philips War, that is, during the second and third quarters of the 17th century. The pottery typically includes two or four rim castellations, marked by molded figures or geometric patterns possibly representing the corn maiden motif, common to Iroquoian pottery of the same period. It is often decorated with attached medallions, protrusions typically decorated with an incised slit motif, above which typically occurs obliquely incised striations. This description is an excellent fit to the ca. 300 sherds of pottery recovered from the cellar fill at the Hollister site. The presence of these large sherds with other English material culture remains indicates that the Hollister family possessed more than one locally manufactured Native American pottery vessel, and that these were eventually discarded with other debris into the abandoned cellar holes at the site. Herrick also pointed to her GPR work indicating a probable area of Native American habitation at the south end of the site, further indicating that a complex relationship existed between the Hollisters and one or more Wangunk families who possibly resided very near the core settlement area of the farm for a number of generations.

Material and Identity

Megan Willison (UConn) finished the session with a talk titled “Identifying Status and Identity through Material Remains.” Willison’s core research questions were: 1) how can status and identity be inferred from artifacts? 2) how do artifact groupings inform archaeologists about life in the past? and 3) how does this information bolster written or oral accounts of the inhabitants of the Hollister site? Willison summarized theoretical concerns including the cultural biography of objects, issues of materiality and identity, and the concept of cultural entanglement theory. Cultural entanglement theory is fast supplanting older concepts of acculturation that tended to deemphasize the active role of Native American people and their culture during the colonial period. Cultural entanglement theory promotes a discussion of power relationships and cultural fluidity between groups – especially during periods such as the 17th century when Native Americans outnumbered the English and the ultimate outcome of the colonial enterprise was not yet clear. Willison noted the presence of both Native American pottery on the one hand and window glass and examples of high-status ceramics such as the north Italian marbleized slipware to discuss the complex expressions of materiality and identity at the Hollister site situated at both the physical and cultural frontiers of Native American and English society.

To conclude I just want to express how proud I was of all of the session participants for their hard work and excellent presentations. First, I’d like to thank Fiona Jones for managing the projector which kept the talks running smoothly. I also want to be sure to thank Mark Packard and his family for permitting us to continue work at this extremely important and increasingly remarkable site. I would also be remiss not to mention the support of the Historical Society of Glastonbury, in particular Jim Bennett and Diane Hoover who have actively promoted work at the site. Finally, this session would not have been possible without the financial support of Mr. Bob Hollister, a Hollister family descendant who very graciously provided funding that supported the research behind many of the talks presented at this session.

Introduction

Introduction